Last Updated on January 22, 2024

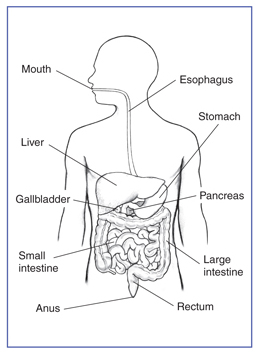

What is the digestive system?

The digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract—also called the digestive tract—and the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. The GI tract is a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus. The hollow organs that make up the GI tract are the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine—which includes the rectum—and anus. Food enters the mouth and passes to the anus through the hollow organs of the GI tract. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system. The digestive system helps the body digest food.

Bacteria in the GI tract, also called gut flora or microbiome, help with digestion. Parts of the nervous and circulatory systems also play roles in the digestive process. Together, a combination of nerves, hormones, bacteria, blood, and the organs of the digestive system completes the complex task of digesting the foods and liquids a person consumes each day.

Why is digestion important?

Digestion is important for breaking down food into nutrients, which the body uses for energy, growth, and cell repair. Food and drink must be changed into smaller molecules of nutrients before the blood absorbs them and carries them to cells throughout the body. The body breaks down nutrients from food and drink into carbohydrates, protein, fats, and vitamins.

Carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are the sugars, starches, and fiber found in many foods. Carbohydrates are called simple or complex, depending on their chemical structure. Simple carbohydrates include sugars found naturally in foods such as fruits, vegetables, milk, and milk products, as well as sugars added during food processing. Complex carbohydrates are starches and fiber found in whole-grain breads and cereals, starchy vegetables, and legumes. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, recommends that 45 to 65 percent of total daily calories come from carbohydrates.1

Protein. Foods such as meat, eggs, and beans consist of large molecules of protein that the body digests into smaller molecules called amino acids. The body absorbs amino acids through the small intestine into the blood, which then carries them throughout the body. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010,recommends that 10 to 35 percent of total daily calories come from protein.1

Fats. Fat molecules are a rich source of energy for the body and help the body absorb vitamins. Oils, such as corn, canola, olive, safflower, soybean, and sunflower, are examples of healthy fats. Butter, shortening, and snack foods are examples of less healthy fats. During digestion, the body breaks down fat molecules into fatty acids and glycerol. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, recommends that 20 to 35 percent of total daily calories come from fat.1

Vitamins. Scientists classify vitamins by the fluid in which they dissolve. Water-soluble vitamins include all the B vitamins and vitamin C. Fat-soluble vitamins include vitamins A, D, E, and K. Each vitamin has a different role in the body’s growth and health. The body stores fat-soluble vitamins in the liver and fatty tissues, whereas the body does not easily store water-soluble vitamins and flushes out the extra in the urine. Read more about vitamins on the Office of Dietary Supplements website at www.ods.od.nih.gov.

1U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010.

How does digestion work?

Digestion works by moving food through the GI tract. Digestion begins in the mouth with chewing and ends in the small intestine. As food passes through the GI tract, it mixes with digestive juices, causing large molecules of food to break down into smaller molecules. The body then absorbs these smaller molecules through the walls of the small intestine into the bloodstream, which delivers them to the rest of the body. Waste products of digestion pass through the large intestine and out of the body as a solid matter called stool.

Table 1 shows the parts of the digestive process performed by each digestive organ, including movement of food, type of digestive juice used, and food particles broken down by that organ.

Table 1. The digestive process

| Organ | Movement | Digestive Juices Used | Food Particles Broken Down |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouth | Chewing | Saliva | Starches |

| Esophagus | Swallowing | None | None |

| Stomach | Upper muscle in stomach relaxes to let food enter and lower muscle mixes food with digestive juice | Stomach acid | Protein |

| Small intestine | Peristalsis | Small intestine digestive juice | Starches, protein, and carbohydrates |

| Pancreas | None | Pancreatic juice | Starches, fats, and protein |

| Liver | None | Bile acids | Fats |

How does food move through the GI tract?

The large, hollow organs of the GI tract contain a layer of muscle that enables their walls to move. The movement of organ walls—called peristalsis—propels food and liquid through the GI tract and mixes the contents within each organ. Peristalsis looks like an ocean wave traveling through the muscle as it contracts and relaxes.

Esophagus. When a person swallows, food pushes into the esophagus, the muscular tube that carries food and liquids from the mouth to the stomach. Once swallowing begins, it becomes involuntary and proceeds under the control of the esophagus and brain. The lower esophageal sphincter, a ringlike muscle at the junction of the esophagus and stomach, controls the passage of food and liquid between the esophagus and stomach. As food approaches the closed sphincter, the muscle relaxes and lets food pass through to the stomach.

Stomach. The stomach stores swallowed food and liquid, mixes the food and liquid with digestive juice it produces, and slowly empties its contents, called chyme, into the small intestine. The muscle of the upper part of the stomach relaxes to accept large volumes of swallowed material from the esophagus. The muscle of the lower part of the stomach mixes the food and liquid with digestive juice.

Small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with digestive juices from the pancreas, liver, and intestine and push the mixture forward to help with further digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb the digested nutrients into the bloodstream. The blood delivers the nutrients to the rest of the body.

Large intestine. The waste products of the digestive process include undigested parts of food and older cells from the GI tract lining. Muscles push these waste products into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water and any remaining nutrients and changes the waste from liquid into stool. The rectum stores stool until it pushes stool out of the body during a bowel movement.

How do digestive juices in each organ of the GI tract break down food?

Digestive juices contain enzymes—substances that speed up chemical reactions in the body—that break food down into different nutrients.

Salivary glands. Saliva produced by the salivary glands moistens food so it moves more easily through the esophagus into the stomach. Saliva also contains an enzyme that begins to break down the starches from food.

Glands in the stomach lining. The glands in the stomach lining produce stomach acid and an enzyme that digests protein.

Pancreas. The pancreas produces a juice containing several enzymes that break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in food. The pancreas delivers digestive juice to the small intestine through small tubes called ducts.

Liver. The liver produces a digestive juice called bile. The gallbladder stores bile between meals. When a person eats, the gallbladder squeezes bile through the bile ducts, which connect the gallbladder and liver to the small intestine. The bile mixes with the fat in food. The bile acids dissolve fat into the watery contents of the intestine, much like how detergents dissolve grease from a frying pan, so the intestinal and pancreatic enzymes can digest the fat molecules.

Small intestine. Digestive juice produced by the small intestine combines with pancreatic juice and bile to complete digestion. The body completes the breakdown of proteins, and the final breakdown of starches produces glucose molecules that absorb into the blood. Bacteria in the small intestine produce some of the enzymes needed to digest carbohydrates.

What happens to the digested food molecules?

The small intestine absorbs most digested food molecules, as well as water and minerals, and passes them on to other parts of the body for storage or further chemical change. Specialized cells help absorbed materials cross the intestinal lining into the bloodstream. The bloodstream carries simple sugars, amino acids, glycerol, and some vitamins and salts to the liver. The lymphatic system, a network of vessels that carry white blood cells and a fluid called lymph throughout the body, absorbs fatty acids and vitamins.

How is the digestive process controlled?

Hormone and nerve regulators control the digestive process.

Hormone Regulators

The cells in the lining of the stomach and small intestine produce and release hormones that control the functions of the digestive system. These hormones stimulate production of digestive juices and regulate appetite.

Nerve Regulators

Two types of nerves help control the action of the digestive system: extrinsic and intrinsic nerves.

Extrinsic, or outside, nerves connect the digestive organs to the brain and spinal cord. These nerves release chemicals that cause the muscle layer of the GI tract to either contract or relax, depending on whether food needs digesting. The intrinsic, or inside, nerves within the GI tract are triggered when food stretches the walls of the hollow organs. The nerves release many different substances that speed up or delay the movement of food and the production of digestive juices.

Points to Remember

- Digestion is important for breaking down food into nutrients, which the body uses for energy, growth, and cell repair.

- Digestion works by moving food through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- Digestion begins in the mouth with chewing and ends in the small intestine.

- As food passes through the GI tract, it mixes with digestive juices, causing large molecules of food to break down into smaller molecules. The body then absorbs these smaller molecules through the walls of the small intestine into the bloodstream, which delivers them to the rest of the body.

- Waste products of digestion pass through the large intestine and out of the body as a solid matter called stool.

- Digestive juices contain enzymes that break food down into different nutrients.

- The small intestine absorbs most digested food molecules, as well as water and minerals, and passes them on to other parts of the body for storage or further chemical change. Hormone and nerve regulators control the digestive process.

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

This information may contain content about medications and, when taken as prescribed, the conditions they treat. When prepared, this content included the most current information available. For updates or for questions about any medications, contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration toll-free at 1-888-INFO-FDA (1-888-463-6332) or visit www.fda.gov. Consult your health care provider for more information.

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. The NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings through its clearinghouses and education programs to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by the NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Michael Wallace, M.D., M.P.H., Mayo Clinic

This information is not copyrighted. The NIDDK encourages people to share this content freely.

Syndicated Content Details:

Source URL: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/Anatomy/your-digestive-system/Pages/anatomy.aspx

Source Agency: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)